China’s Loan Policy Toward a Volatile Venezuela:

Balancing Economic Interests and Energy Security with Noninterference

Cory J. Combs

Johns Hopkins SAIS

Submitted for Course “Chinese Foreign Policy”

Professor David M. Lampton | JHU SAIS Hyman Professor and Director of SAIS-China and China Studies

October 23, 2017 (Edited November 26, 2018)

Original Word Count: 1977

Grade: A

Executive Summary

The Venezuelan crisis challenges China’s commitment to noninterference; conversely, it could provide China an opportunity to demonstrate global leadership, should it intervene in Maduro’s destabilizing activities. Ultimately, the balance of China’s interests will likely result in hedging of its oil-backed loans to Venezuela, but without their discontinuation. China will try to avoid appearances of political interference, eager to prove its noninterference as a source of legitimacy with developing countries, many of which it aims to partner with for the Belt and Road Initiative. Further, the Party under Xi Jinping will not pursue ideological kinship with Maduro, and while it will not intentionally hasten his fall, nor will it prevent it. The ideal scenario for China will be for loans to keep Maduro’s regime minimally viable until nonfinancial forces induce regime change.

History and Development

In 1999, Hugo Chavez and Jiang Zemin established a strategic partnership that would guide the massive expansion of engagement under Hu Jintao from 2002 to 2012. China’s expanded engagement centered around oil-backed loans which bolstered China’s energy supply security and grounded China’s efforts to increase its presence in Latin America.

Throughout the 2000s, Venezuela was a key regional power. Chavez vowed to free Venezuela from elite rule and purge the region of capitalist, particularly U.S., influence, as part of his Bolivarian Revolution. Highly charismatic, Chavez personified the state, presenting himself as a “martyr” of the Venezuelan people in a “missionary” role of raising them to a position of pride.

An anti-capitalist state with large social welfare expenditures, Venezuela relied on oil holdings for funding. The environment under Chavez offered China a rational opportunity for investment; China quickly became Venezuela’s largest creditor. Since 2005, China’s policy banks have provided it $62.2 billion in oil-backed loans. China has become Venezuela’s second-largest trading partner, with trade ballooning from $175 million in 1999 to $20 billion in 2012, when Xi Jinping took power. Chavez died in 2013 and his chosen successor Nicolas Maduro was elected.

In stark contrast to the Venezuela in which China began to invest, the viability of the Venezuelan state under Maduro is rapidly eroding. Oil prices have plummeted since the Hu-Chavez era, dropping from $120 per barrel in 2007 to less than half that in recent years. OPEC has been either unwilling or unable to increase prices for most of this time. Maduro’s continuation of the Bolivarian Revolution’s far-left economic policies, alongside the precipitous drop in oil prices, has cause widespread shortages of food, essential goods, and even health services.

Maduro, trying to maintain political control without changing economic policy, has resorted to increasing levels of authoritarianism. In 2015, for example, he overturned democratic election results, and later declared the National Assembly unconstitutional, with the results of widespread social upheaval and violent opposition.

By 2016, the crisis had prompted unprecedented action from Latin American multilateral institutions: regional trade bloc MERCOSUR suspended Venezuela, and the head of the Organization of American States (OAS) recommended Venezuela’s suspension if Maduro failed to hold and observe democratic elections, prompting Maduro to pre-emptively withdraw Venezuela’s membership.

Far from ameliorating the economic damage of dropping oil prices, Maduro has led Venezuela into political and social crises and increasing regional isolation that exacerbates the issue. IMF data for Venezuela shows inflation soaring at 652.7% and real GDP shrinking at 12% annually. The region, now broadly aligned in condemning Maduro as a rising authoritarian, fears a full-blown humanitarian crisis.

The Venezuelan and Latin American environments today, then, are very different from when China began its investments. Due to the economic crisis, China’s policy banks face considerable financial cost and loss of legitimacy if Venezuela defaults, as seems increasingly likely. If Venezuela cannot keep up production, China also stands to lose energy supply security.

The political value of Venezuela as an inlet to broader Latin American influence is all but lost; indeed, with continued engagement China risks appearing to contribute to the developing humanitarian crisis or to support a rising authoritarian.

However, China is also firmly committed to noninterference: Xi’s vision of China as an economically powerful partner that will not interfere in partners’ domestic affairs is a key component of the Belt and Road Initiative’s intended appeal. The Initiative is in turn a core element of Xi’s vision for China’s global leadership; its legitimacy is a vital strategic interest.

While China could use its considerable financial leverage in Venezuela, whether to protect its investments or to benefit the region, doing so would risk undermining its overarching aims.

China under Xi has generally continued to support Maduro, even announcing new development projects and publicly defending Venezuela amidst international condemnation. In 2016, however, China unofficially reached out to Maduro’s political opposition, likely (though it cannot yet be confirmed) seeking assurances that loans would still be repaid should Maduro be ousted. Further, it has denied at least one request for a relaxation of loan terms, likely seeking to avoid similar requests from other countries to which it has given energy-backed loans.

Given Venezuela’s highly volatile political situation, China has quietly begun to hedge its bets. Nonetheless, its intentions beyond the 19th Party Congress, in Xi’s second term, will remain unclear until the Congress concludes, with some aspects possibly remaining opaque until the 13th National People’s Congress in March 2018, when officials are formally appointed.

Formation of China’s Venezuela Policy

Framework

China’s foreign policy is the result of a complex confluence of actors and forces. The following points provide the core framework for analysis and subsequent recommendations:

While policies are often attributed to “China” as shorthand, the policy formulation and implementation are both far less centralized than the strict hierarchy of authority in the PRC suggests. Specific foreign policies are formally governed by one or more of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the Chinese Government, and, depending on the issue, by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). However, to these are added a number of additional actors that vie for influence, including “resource companies, financial institutions, local governments, research organizations, the media and netizens.”

Contemporary Chinese leaders reach decisions through a complex, opaque, high-level bargaining process. The process does not imply equality among actors; established interests often employ diverse forms of leverage to preserve spheres of influence. While decisions are often attributed to one source, though, they typically reflect further interests involved in the bargaining process. Fully tracing influences is a precarious project.

The overall centralized hierarchical structure of China’s governance, coupled with the sheer scale of China’s administrative units, has resulted in a vast bureaucracy that divides labor and allocates resources at many levels of specificity, from national to town-level. However, there is much interplay among the divisions, necessitating what scholar David Lampton calls “cross-system integrators,” i.e. institutions that can coordinate action across bodies with distinct roles in related areas. The result is an expansion of an already vast bureaucracy. As some researchers have noted, “Arguably, bureaucracy is the next major player in the policy-making process in China after the top leaders.”

Thus, the hierarchical structure and multilayered bureaucratic web (3) enable gaps in which the bargaining processes can take place (2) among various leading actors (1); and so, in broad strokes, China’s policies are forged.

Key Influences on China’s Venezuela Policy

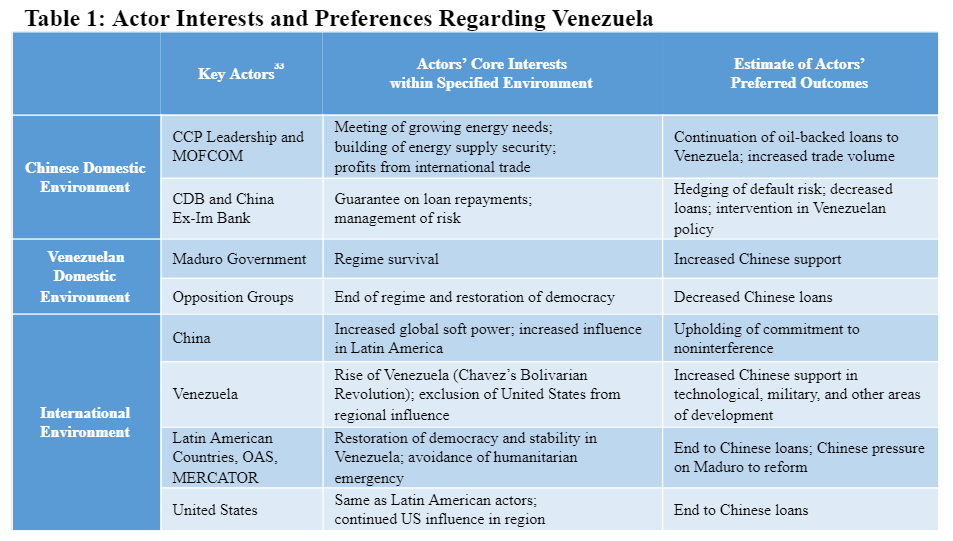

Chinese policy toward Venezuela is shaped by forces in three distinct environments: the Chinese domestic environment, the Venezuelan domestic environment, and the international environment.

The core Chinese actors are the CCP leadership, the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), and the China Development Bank (CDB) and the China Ex-Im Bank, both of which are commercial. China’s energy institutions are evolving but still fragmented and weak, and so have yet to secure a notable policy-making role among the established bureaucratic powers.

In Venezuela, Maduro has overriding control over policy; however, unofficial Chinese envoys have reached out to opposition leader Henrique Capriles, indicating that the opposition is indeed part of China’s considerations.

In the international environment, we must consider: China’s intentions in Latin America and on the international stage; Maduro’s goals on the international stage; Latin America’s general response to the crisis; and the U.S. interest in stability. The latter two are critical to the overall international pressure Venezuela and China face, both on a bilateral basis and as regards the United Nations and regional blocs such as MERCOSUR, which as of August 5 has suspended Venezuela in an effort to pressure Maduro to restore democracy.

These environments, the key actors, their core interests and estimates of their preferred outcomes are summarized in Table 1:

China alone has significant interests in both expanding and ceasing loans. So far it has stopped increasing, but generally maintained, its funding. Ultimately, how China changes its loans to Venezuela depends on two factors: how Xi Jinping and the rest of the CCP’s top leadership judge the balance of forces summarized in Table 1, and the outcomes of the bargaining process between CCP leaders, the CDB, the Ex-Im Bank, and the lesser bureaucratic elements at play.

Final Analysis

Matt Ferchen summarizes China’s role in the Venezuelan crisis, and how it might correct course:

China has not been blameless, its banks and oil companies misunderstood and miscalculated the direction and instability of Venezuelan politics and economic management, and so failed to anticipate the inevitable and harmful effects on Venezuelan oil management and output. Going forward, the immediate future for China-Venezuela oil ties rests on whether China is willing and able to work with Venezuela and possibly other countries and institutions to help put Venezuela and its oil industry on a more sustainable path.

Implicit in Ferchen’s analysis is that for China to correct course, it will have to intervene in Venezuela’s governance. The CDB and MOFCOM would likely approve of such a measure, as it would bode well for risk management and lessen the likelihood of default. However, overt interference would undermine noninterference. Further, under Xi, China has made concerted efforts to demonstrate support for Maduro, at least in part to bolster its image as promoting sovereign rights ahead of Belt and Road development. Meaningful intervention is highly unlikely.

Another option would be to continue the present level of loans and wait to see what happens. That, plus hedging, has been Xi’s approach. However, Venezuela’s instability is only growing, with the IMF now predicting hyperinflation; it is unclear whether Maduro can stay in power indefinitely. Purely economic calculation thus opposes continued lending. China is nevertheless more likely to maintain the status quo, which may prove enough to keep Maduro’s government minimally viable for the near future. If the state reaches the point of imminent failure, China will have little ideological motive to support Maduro or otherwise intervene. Thus, China is unlikely either to intentionally hasten Maduro’s fall or to do much to prevent it. Instead, only increased efforts to secure repayment guarantees should be expected.

The same analysis of influences on China’s foreign policy suggests that China will have very little willingness to assist Latin American neighbors and the United States in any recovery process, outside of a UN mission. China prefers bilateral to multilateral engagement on energy issues, but for political matters it will operate primarily within multilateral institutions, both for minimization of costs and to avoid appearances of heavy-handedness as it builds its image of a constructive emerging world power.

Bibliography

- “Spotlight: China-Venezuela Cooperation Eyes New Development Projects.” Xinhua News Agency, Feb 24, 2017a. http://english.gov.cn/news/international_exchanges/2017/02/24/content_281475576899884.htm.

- “Venezuela Accuses France’s Macron of ‘Interference’.” AFP International Text Wire in English, Aug 30, 2017b. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1933571143.

- “Venezuela’s Deepening Crisis.” Strategic Comments 23, no. 6 (July 25, 2017c): xii. doi:10.1080/13567888.2017.1358535. http://dx.doi.org.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/10.1080/13567888.2017.1358535.

- “Xinhua Insight: China Strives to be Anchor for World Stability, Globalization.” Xinhua News Agency,March 8, 2017d. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-03/08/c_136113471.htm.

- Balding, Christopher. “Venezuela’s Road to Disaster is Littered with Chinese Cash.” Foreign Policy, June 6, 2017. http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/06/06/venezuelas-road-to-disaster-is-littered-with-chinese-cash/.

- Blanchard, Ben and Michael Perry. “China Offers Support for Strife-Torn Venezuela at United Nations.” Reuters, September 20, 2017. http://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asiapacific/china-offers-support-for-strife-torn-venezuela-at-united-nations-9233220.

- Chang, Felix K. Limits of Chinese Friendship: China’s Development Loans to Venezuela. Philadelphia: Foreign Policy Research Institute, 2016. https://www.fpri.org/2016/07/limits-chinese-friendship-chinas-development-loans-venezuela/#_ftn1.

- Cunningham, Nick. “Why OPEC Couldn’T Move Oil Prices Higher.” Nasdaq, May 26, 2017. http://www.nasdaq.com/article/why-opec-couldnt-move-oil-prices-higher-cm795053.

- Dollar, David. “China’s Investment in Latin America.” Brookings Institution Reports (January, 2017). https://search.proquest.com/docview/1881434114.

- Downs, Erica S. Inside China, Inc: China Development Bank’s Cross-Border Energy Deals: Brookings Institution, 2011.

- Ferchen, Matt. “Can China Help Fix Venezuela?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Jul 24, 2017). https://search.proquest.com/docview/1923458073.

- ———. “How Critical is China’s Lifeline to Venezuela?” (September 26, 2016a). http://carnegietsinghua.org/2016/09/26/how-critical-is-china-s-lifeline-to-venezuela-pub-64712.

- ———. “Will Latin American and China’s Energy Partnership Change?” Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy (April 7, 2016b). http://carnegietsinghua.org/2016/04/07/will-latin-america-and-china-s-energy-partnership-change-pub-63276.

- Gallagher, Kevin P. and Margaret Myers. “China-Latin America Finance Database.” Inter-American Dialogue. https://www.thedialogue.org/map_list/.

- Gosset, David and Temir Porras Ponceleo. “Strong Strategic Partnership.” China Daily Europe, September 23, 2013. http://europe.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2013-09/23/content_16986191.htm.

- Hornby, Lucy and Andres Schipani. “China Seeks to Renegotiate Venezuela Loans; Beijing’s Envoys Seek Assurances from Opposition on Debt in Case President Falls.” Financial Times, June 19, 2016. https://www.ft.com/content/18169fbe-33da-11e6-bda0-04585c31b153?mhq5j=e5.

- Hsiang, Antonio C. “China and the Venezuela Crisis.” The Diplomat (July 24, 2017). https://thediplomat.com/2017/07/china-and-the-venezuela-crisis/.

- International Monetary Fund. “Latin America’s Recovery on Track but Long-Term Growth Weak.” http://www.imf.org/en/news/articles/2017/10/13/na101317-latin-americas-recovery-on-track-but-long-term-growth-weak.

- ———. “Republica Bolivariana De Venezuela and the IMF: Country Data.” http://www.imf.org/en/Countries/VEN.

- Jakobson, Linda and Dean Knox. New Foreign Policy Actors in China. Solna, Sweden: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2010.

- Koerner, Lucas. “Venezuela and China Sign New $2.7 Billion Development Deal.” February 15, 2017. https://venezuelanalysis.com/news/12931.

- Kong, Bo. “Governing China’s Energy in the Context of Global Governance.” Global Policy 2, Special (September, 2011): 51-65.

- ———. “Institutional Insecurity.” China Security 2, no. 2 (2006): 64-88. https://www.issuelab.org/resources/374/374.pdf.

- Krygier, Rachelle and Anthony Faiola. “Maduro Defends Election Results, Claims Opposition by U.S. is Aiding Him.” The Washington Post, Oct 17, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1951813151.

- Lai, Hongyi and Su-Jeong Kang. “Domestic Bureaucratic Politics and Chinese Foreign Policy.” Journal of Contemporary China 23, no. 86 (October 4, 2014): 294-313. doi:10.1080/10670564.2013.832531. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2013.832531.

- Lieberthal, Kenneth and David M. Lampton. Bureaucracy, Politics, and Decision Making in Post-Mao China. Studies on China. Vol. 14. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

- Magnier, Mark. “China Dials Back its Lending to Wobbly Venezuela.” The Wall Street Journal, February 24, 2017. https://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2017/02/24/china-dials-back-its-lending-to-wobbly-venezuela/.

- Mallett-Outtrim, Ryan. “China Urges Respect for Venezuela’s Sovereignty.” Venezuelanalysis.com, May 4, 2017. https://venezuelanalysis.com/news/13102.

- Rios, Xulio. “China and Venezuela: Ambitions and Complexities of an Improving Relationship.” East Asia: An International Quarterly 30, no. 1 (January 6, 2013): 53. doi:10.1007/s12140-012-9185-0. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=tsh&AN=85974931&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- Romero, Carlos A. and Víctor M. Mijares. “From Chávez to Maduro: Continuity and Change in Venezuelan Foreign Policy.” Contexto Internacional 38, no. 1 (Jun, 2016): 165-201. doi:10.1590/S0102-8529.2016380100005. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1814293737.

- Shambaugh, David. “China’s Soft-Power Push.” Foreign Affairs 94, no. 4 (2015): 99. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f5h&AN=103175014&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- Shifter, Michael. “Venezuela’s Bad Neighbor Policy.” Foreign Affairs (May 5, 2017). https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/venezuela/2017-05-05/venezuelas-bad-neighbor-policy.

- Thies, Cameron G. “Role Theory and Foreign Policy Analysis in Latin America.” Foreign Policy Analysis 13, no. 3 (July 1, 2017): 662-681. https://doi.org.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/10.1111/fpa.12072.

- Vyas, Kejal. “China Rethinks its Alliance with Reeling Venezuela.” The Wall Street Journal, Sep 11, 2016. https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-rethinks-its-alliance-with-reeling-venezuela-1473628506.

- ———. “OAS Chief Urges Suspension of Venezuela’s Membership; Secretary-General Luis Almagro Calls on President Maduro to Hold Elections, Take Measures to Support Democracy to Avoid Possible Suspension.” Wall Street Journal, Mar 14, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1876942584.

- Yang, Jiechi. Innovations in China’s Diplomatic Theory and Practice Under New Conditions. Geneva: Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the United Nations Office at Geneva and Other International Organizations in Switzerland, 2013. http://www.china-un.ch/eng/bjzl/t1067228.htm.

- Zhang, Chun. “Latin America’s Oil-Dependent States Struggle to Repay Chines Debts.” Chinadialogue, April 12, 2017. https://chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/9730-Latin-America-s-oil-dependent-states-struggling-to-repay-Chinese-debts.

Twitter Facebook Google+